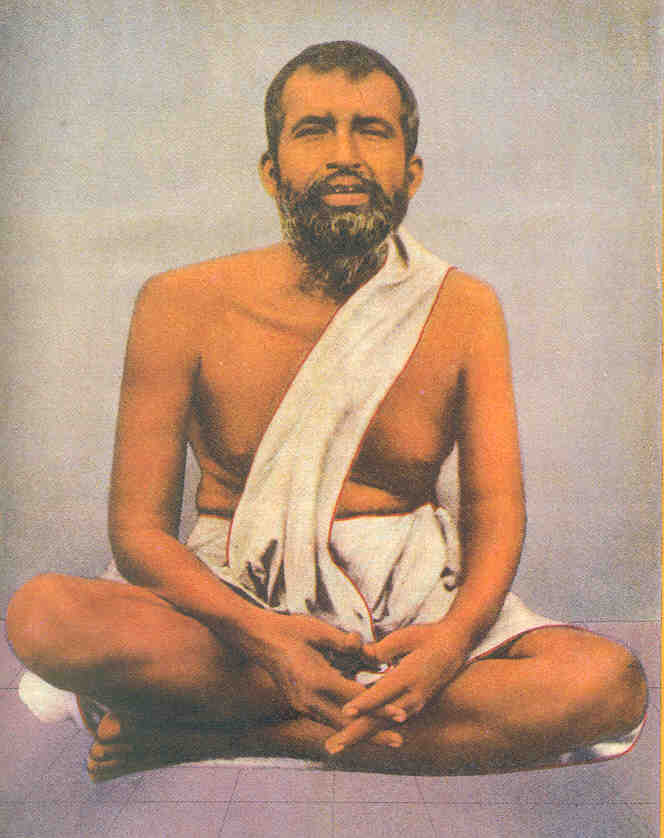

The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna :24.

RELATION WITH HIS WIFE : In 1872 Sarada Devi paid her first visit to her husband at Dakshineswar. Four years earlier she had seen him at Kamarpukur and had tasted the bliss of his divine company. Since then she had become even more gentle, tender, introspective, serious, and unselfish. She had heard many rumours about her husband's insanity. People had shown her pity in her misfortune. The more she thought, the more she felt that her duty was to be with him, giving him, in whatever measure she could, a wife's devoted service. She was now eighteen years old. Accompanied by her father, she arrived at Dakshineswar, having come on foot the distance of eighty miles. She had had an attack of fever on the way. When she arrived at the temple garden the Master said sorrowfully: "Ah! You have come too late. My Mathur is no longer here to look after you." Mathur had passed away the previous year. The Master took up the duty of instructing his young wife, and this ...

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment