The Twofold Character of Cosmic Life :

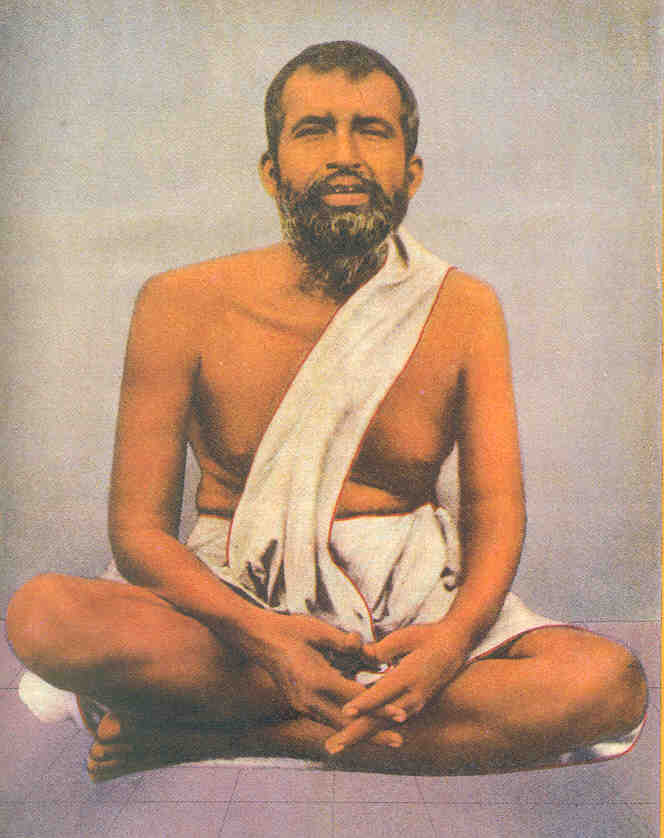

Swami Krishnananda.

Srimad Bhagavadgeeta : Chapter-15. Purushothamayogam:- Part-1. ( Aswatham)

Sadhakas and seekers of truth from various parts of the country come to this holy abode in search of a mysterious something, the acquisition of which is considered as a rectifying factor or a remedy for the various illnesses of life. They have not come here for nothing. It is taken for granted that their search is for a light, and not a substance or object. They seek an enlightenment, a torch to illumine the path which they have to walk in the various fields of their activities.

There are doubts and difficulties, problems galore, so that it becomes difficult to take even one step ahead on account of a pitch darkness throughout the horizon that appears to be hanging heavy before our eyes, which is apparently a common fact in the life of each and every person. It does not appear that we are asking for any particular thing in this world. We seem to be asking for enlightenment and light so that we may move in the direction that is proper, lest we should move in an erroneous direction and fall into a pit.

Our notion that we are asking for things is basically an error. We are neither asking for food, clothing and shelter, nor for company of people, nor for wealth, nor even for a lengthened life in this world, notwithstanding the fact that it appears we are asking for these things. There is a sorrow that is seeping into the very veins of our personality, and we try to get over this problem of sorrow by various means, just as a patient goes to various doctors under the impression that a physician will be able to cure his sorrow of disease. If he is not satisfied with one physician, he goes to another. He goes to a multitude of physicians in search of a cure for his ailment.

This is exactly what we are doing. We are in search of a cure for the sorrows of life, which is nothing but the illness of life, and we run to various places and personalities as patients go to doctors in search of recipes or magic prescriptions which can instantaneously place us in a haven of happiness and freedom. Neither are we able to diagnose the nature of the illness of our life, nor can it be said that we are in a position to understand what sort of happiness we are seeking. We have a very hazy notion of both these sides of life.

What is the sorrow that is hanging heavily on our heads is not a question easy to answer. At one moment it may appear that the grief is of one type, and at another moment it is another type. It changes its colour like a chameleon, and we are under the impression thereby that perhaps there are millions of sorrows. Not so is the case. The sorrow is a single structural or organic defect of personality which ramifies itself into various expressions of inconvenience to our personality, and which goes by the name of sorrow, grief, suffering, pain, and so forth.

There is a basic illness which is deeply rooted in us, and we have not the time or the patience to go into the abyss of this sorrow. We seek immediate relief, as is the case with physical illness. There is an asking for an immediate remedy for an acute case of suffering, and this is human nature. The sorrow cannot be borne any further for a longer period, and so we ask for immediate prescriptions of medicine for our grief, and these are what the world gives to us in the form of experiences.

Unfortunately for us, we are mistaken in the very approach that we are adopting in the redress of our sorrows. No amount of running to doctors of divinity will be able to keep us in that haven of bliss which we are apparently striving for. The world has been what it was, and it has not given any indication that there has been any change in its structure. Perhaps right from creation up to this day nature does not appear to have changed its colours.

But we are endlessly hoping for something, we know not what. There is an endless agony in the hearts of people. Not one individual through the process of history can be said to have passed a life of perennial freedom from birth to death. There have been thorns under the feet of everyone, though the search was for roses, milk and honey in the world. There is a chaotic approach of the mental structure of man. There is confusion in our brains and anxiety in our hearts, and darkness before us.

Well, this is to give an outline of the picture of the life that we are living in this world and the way in which we are trying to acquire freedom and happiness, not knowing the basic structure of the various problems of life. A good physician is supposed to be one who knows the location of the main switchboard in the personality of the human being, by operating which the whole panorama of experiences can be visualised at one stroke.

A disease is a structural maladjustment, and it appears in the form of an agony to the consciousness. When there is a lack of an alignment between our mind, or consciousness, and the nature of our experiences in life, there is what we call unhappiness. Happiness is nothing but the organic alignment of our mind with the various patterns of human experience. When there is a lack of this alignment a jarring sound is produced, as a loudspeaker sometimes makes a noise. There is some kind of defect in the alignment of the internal mechanism. When the mechanism of our psyche in its relation to the structure of the whole of experience in the world goes out of gear, there is unhappiness because happiness is alignment, and unhappiness is the opposite of it. As Ayurveda physicians tell us, health is the harmony among the humours of the body: vata, pitta, kapha. When the sattva, rajas, tamas qualities are in a state of balance, we are supposed to be enjoying mental as well as physical health. So is the case with every kind of happiness. There is a necessity to put the mechanism of life in order, to streamline the way of the working of the mind in its relation to the various shapes that life takes.

All this, when it is enquired into profoundly, will naturally go over the heads of people. We are not taught to think in this manner. We have an education which is supposed to be for earning our bread; today it has failed even to earn our bread, and it has not succeeded in getting anything worth the while. We are in sorrow in the beginning, we are in sorrow in the middle, and we are in sorrow at the end. That is all we see in life. The shape of sorrow may change, but it is there in one form or the other. Whether our creditor is this man or that man, it makes no difference; we have a creditor at our door, and that is enough for us. It does not matter which person it is and when he will come and stand at our gate. So is the sorrow of life.

There is, therefore, a need to be serious in our pursuits and not to continue to behave like babies or children asking for toys, which are only a temporary relief for their tears. We give a toy to the child, and it stops crying. Why it cries, nobody knows. These toys are temporary contrivances to suppress the outward expression of the sorrow of the child, but the inner difficulty persists whatever be the outer adjustments we make in the various walks of life.

The various outer adjustments are well known. The gaining of wealth, making money, increasing the bank balance, getting a good job, enhancement of status of oneself in human society, dainty dishes, palatial houses, vast gardens, and so forth, are the avenues of approach of the mind that seeks immediate relief. We have seen people with large areas of land. Are they happy? We have seen people with large bank balances. Are they happy? We have seen people with everything that the world can give, but they are grief-stricken for a cause they cannot explain, and nobody can explain.

In the commencing verses of the Fifteenth Chapter of the Bhagavadgita we have a complete picture of the whole of life in every one of its aspects. The way in which the Fifteenth Chapter of the Bhagavadgita starts is the way in which we have to start thinking if our thinking is to be right thinking. We are used to thinking in terms of family, relations and properties, but in these verses of the Fifteenth Chapter, the Bhagavadgita does not think in terms of families and relations, of I and mine, of property, belonging, friend and foe. There is a magnificent picture before our mental eye. The whole world is placed before us in a nutshell.

The analogy the Bhagavadgita places before us to explain the nature of life as a whole is the well-known analogy of a tree. The whole of life is compared to a large tree spreading itself in every place, in and out of things, and extending from heaven to the nether regions: ūrdhvamūlam adhaḥśākham (Gita 15.1). We have never seen a tree of this type whose roots are above and branches are below. It is an unthinkable tree. How can the roots be above in the skies and the branches be below on the Earth? But such is the tree which life is.

This tree is taken as the example of the structure of life because of the way in which the tree grows. Life is a growing process and a movement with the power of the waves of an ocean rumbling within its own bosom, urging itself forward in a direction which is spread out everywhere in all places. The growth of life is not in any particular linear direction. It is an all-round movement, like the growth of our own body. When we grow into an adult from a baby, we do not move only vertically or horizontally, but in every aspect—inwardly and outwardly—in a balanced manner.

The creative evolution of life, into which great research has been made in modern times by philosophers such as Bergson, is a tendency to move in every direction, outwardly expressing its power of vitality for a purpose which the human mind cannot properly envisage. When we grow, we do not know what we are growing into, and to what purpose. Why should we become an adult? Who has written this, in which scripture? Why should we not remain as a baby? What is the harm? Let us all be babies and never grow, or let us be born as youths. Why should we be born as babies and then grow into youths, and then have this agonising decrepitude of senile ataxia? What is all this mystery? Why should there be this growth of anything or everything? What is the direction which things are appearing to take? Why should the tree grow? Why should man prolong his life up to a certain limit and then disappear from the Earthly scene, not knowing even the time of his disappearance? What is this tremendous impulse in us which keeps us expecting something noble in the future, though that future may be cut short in one moment by the icy hands of nature?

We know very well that our Earthly life can come to an end at any moment, but we never take it very seriously. We can take it seriously if it goes so deeply into our hearts that we will not be able to breathe even for a few seconds. Something in us overpowers this instinct of the awareness of the impending discontinuity of life, and we are instinctively compelled to brush aside this immanent catastrophe of what we call death that may descend upon us at any moment of time.

While there is on one side the instinct of the consciousness of death and destruction, there is also another kind of instinct which keeps us completely forgetful of this phenomenon of life. We would very much wish to forget that there is such a thing called death. Nobody would like to think there is such a thing as that because it hangs before us as an ominous horror.

Now, a reality cannot be forgotten. If death and destruction and annihilation of Earthly existence is to be an end of all things, if that is a reality by itself, there cannot be another reality overcoming it. But there is something in us which somehow or other overwhelms this instinct of destruction and sorrow, and tells us that life need not necessarily be equated with all sorrow. If it is concluded once and for all that life is only sorrow and an ocean of suffering, and there cannot be anything else but that, then there cannot be any such thing as the instinct of hope for a better future. But who does not hope for a better future? So we have in us a mysterious and tremendous impulse for what we may call an immortal pursuit of the ultimate success in life, though what is visible to our eyes is only darkness and pain.

The comparison that the Bhagavadgita gives is significant. The growth of the tree is from the seed towards its trunk and branches and the various ramifications thereof. There is the impulse of external expression in the tree. It moves towards the sky, if we can take the example of our own trees on Earth. The seed of the tree bursts forth in the direction of an external expression of itself. The tendency of the seed is not to hibernate but to develop the roots and the tendril of the large tree that it is to become later on. The sap which is hidden in the seed urges itself forward in external forms, searching for the light of the sun in extended space. The impulse that is within the tree is the cause behind its manifestation. The tree is in the seed in the form of an impulse, and this impulse seems to be towards diversification. It wants to manifest itself in as many forms of expression as possible, branching off into minute details which cannot be counted.

This urge is present everywhere, not merely in the vegetable kingdom but also in animal life and in human existence. Multiplicity is the objective behind the vital urge of nature as a whole. We cannot understand what this drama is. We want to multiply our wants, multiply our needs, multiply the gadgets that can satisfy our desires, and we ask for an infinite number of things in the world. Infinitude in the sense of a multiplicity of arithmetical computation is perhaps the nature of the impulse that is hidden in life.

This is explained in the very first verse of the Fifteenth Chapter of the Gita. There is the expression of the tree into various branches. What are these branches? The knowledge that we seek, the intelligence that we have, the perceptions which give us satisfaction are the branches of this impulse for self-expression—chandāṁsi yasya parṇāni (Gita 15.1). Chandāṁsi are various types of knowledge, natural as well as supernatural, and it is so because the tree spreads itself not merely in this world of physical experience, but also even in the heavens. Adhaś cordhvaṁ prasṛtāstasya śākhā (Gita 15.2): The branches of this tree spread themselves not merely here on Earth but also above in the heavens. Na tad asti pṛthivyāṁ vā divi deveṣu vā punaḥ, sattvaṁ prakṛtijair muktaṁ yad ebhiḥ syāt tribhir guṇaiḥ (Gita 18.40): Not one thing anywhere, neither in heaven nor on Earth, can be found which is not an expression of the gunas. Guṇapravṛddhā viṣayapravālāḥ (Gita 15.2): The gunas are the forces of externalised expression; the power that drags us outside of ourselves, which pushes us out of our own house and into the space outside, that is the guna.

The gunas of prakriti are the forces which make us a stranger to our own life and aberrant in our own personality, and make us lose our own self. The powers that make us lose our own self and search for that which is not our self are the gunas of prakriti. Just as the sap of the tree moves outwardly in the direction of the ramification of branches, the sap of life moves outwardly in the direction of the ramification of experiences. Therefore, we seek infinitude of experiences. Variety is the spice of life. We are bored of monotony. We know very well we can sit for hours and hours in a movie theatre watching a variety of sound and colour, passing the whole night without a wink of sleep. But if we sit for japa, for instance, chanting one name throughout the night, we will droop down into sleep in half an hour. The mind does not like monotony. It likes variety, but why?

The mind likes variety because it is a slave of this impulse of self-expression into the variety of experience. We are not masters; we are utter slaves of something which is handling us as puppets. This power is everywhere in the world; it is not only in the body of a particular individual. That is why it is called cosmic prakriti. The gunas of prakriti are cosmic powers which compel every individual, right from the lowest electron to the highest orbs of the solar system. All these are dancing like puppets, marionettes, by the strings that are operated upon by these powers of nature called sattva, rajas and tamas, which are the constituents of prakriti.

Visualising this horror of life due to which we seem to have no voice in anything whatsoever in this world, thinkers such as Schopenhauer in the West pictured a dark form before us, and said life is nothing but hell: If you want to see hell, be born into this world. This is the utter despair that sometimes made these thinkers write poems such as the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam which says everything is wind passing; everything is despair, sorrow, straw, sapless and essenceless; now it is, now it is not; there is nothing worthwhile in life.

But the picture of life is not complete merely by seeing the seamy side of things. The problem lies here. The difficulty in understanding life arises merely because of the comprehensiveness of the pattern of life. If it is just one thing before us, we can look at it; but it is so many things, and it is difficult for us to comprehend. Life is not only one side of the picture. It is tremendous sorrow, no doubt, from the aspect of emphasis that we lay on one side of experience; but if it had been only that, we would not have been living here even for three days. Utter sorrow will not permit a person to live in this world even for a few minutes. He will immediately have a heart attack and collapse. But one lives in spite of darkness everywhere and sufferings galore because there is a positivity ruling over the sorrows of life.

This twofold character of cosmic life is presented in these verses of the Bhagavadgita. The first part tells us the problematic structure of the tree of life, and the second part tells us how we can free ourselves from the clutches of this cosmic urge for self-expression and entanglement in objects of sense.

The powers of prakriti are nothing but the powers of the whole of nature. We cannot know what nature is, what prakriti is, because we are a part of it. It is not outside us. This is another difficulty before us. A thing that is outside us can be seen and examined through a microscope or a powerful instrument in a laboratory, but how can we examine that in which we ourselves are involved? A study of nature automatically becomes a study of man. To know things is to know oneself.

This uncomfortable truth automatically follows from the fact of the involvement of human nature in cosmic nature. The world is not outside us, nor is it inside us because as a limb of the body hangs inseparably in its relation to the organism of the body, we hang inseparably in relation to nature as a whole. To understand anything will appear to be like understanding everything, just as to know the structural pattern of one cell in the body would be to know the whole body because of the interrelatedness of the various parts of the whole which it is.

This tree of life which has its roots above and branches below is the evolutionary process of the cosmos. The whole of cosmology is here in two or three verses. The creative will of God is the sap of the tree of life, and if we can compare the will of the Supreme Being to the impulse for self-expression in the seed of a tree, we may naturally conclude that the whole of life is nothing but a tree with all its ramifications.

We are told by the Upanishads and scriptures of this character that the one willed to be many, the seed intended to become the tree. This intention of the seed to become the tree is the desire of life. What we call desire is nothing but the urge of the seed to become the tree. Why does it wish to become the tree? Why should it not exist as a seed alone? What is wrong with being merely a seed? And what does the seed gain by becoming a tree? The whole of the Bhagavadgita is an answer to this question.

Why should we not keep quiet as a seed? Why do we want to become a tree? Why do we peep into nature through the skies and look at the sun for light and air? Why does the tree desire this? Why should we come out of our rooms or peep outside the window to see who and what are there? Why should we want to know? How can we explain this curiosity in our lives? Why is it that we feel like fish out of water within our rooms, and want to go out to other places? Why is it that we are so restless?

Well, the seed is restless. It has to become the tree. We cannot curb its force. Our movements from place to place are nothing but our seed of the mind moving as the branches of the tree of our own experiences. Nobody can rest quiet: na hi kaścit kṣaṇam api jātu tiṣṭhaty akarmakṛt (Gita 3.5). We will go crazy if we are locked up in one room, just as the seed will struggle to burst forth in some way or the other when circumstances for it become favourable.

Unless we are able to know what this mysterious urge is which keeps us always in tenterhooks and never gives us anything, we will not be able to live happily in this world. We may go to any doctors, any Gurus, but we will be the same person. Nobody is going to help us unless the light comes from within us, because our conviction is our guide. Our faith, our stability and logical conclusiveness of approach in life are the satisfaction. Gurus and physicians may show us the way, but they cannot walk for us. We have to walk.

The sorrows of life are the outcome of our subjectness to this urge of life to ramify itself into branches of experience and keep us unhappy nevertheless. If we are to seek for a concrete example of an experience between the devil and the deep sea, here it is before us. To live in this world in this condition is to be exactly between the devil and the deep sea. We cannot keep quiet. We are forced to run out of ourselves in search of various things. That is the deep sea on one side. But after searching for all the things in life, we are still in sorrow. That is the devil on the other side. Not to be seeking for things is sorrow, and not to find anything after the search is another sorrow. So always there is sorrow. Oh, what is this? We do not know whether to exist or not to exist. To be or not to be, is the great question. We cannot live, we cannot die, because to live is great sorrow, and to die is worse than that. We do not know which to choose between these two.

The Bhagavadgita gives the answer. We may have been studying, reading chapters of the Gita, but it is difficult for many people to find time to go into the nature of the answer the Bhagavadgita gives to the various queries that arise from our minds. Otherwise, we would be reading the Bhagavadgita like reading the British Pharmacopoeia from the first page to the last page. It may describe all the drugs that are available anywhere in the world—their composition, their character, and so on—but nothing happens. So would be the study of a scripture, whatever be the scripture, if the import of it is not absorbed into our experience.

Our spiritual sadhana is not a mere activity such as running a shop. It is not a business. People go to ashrams, do something, and go back and do another thing. So it ends in various kinds of doings, but the inner pith of their personality is untouched. They go as they came, which is very unfortunate.

To regard spiritual sadhana as a mere outer activity, without any relation to the inner consciousness of our being, would be to treat typhoid fever by putting on a beautiful shirt. The typhoid fever will not go, even if the shirt is beautiful. Similarly, all sadhana which is purely of an extraneous nature will look beautiful on the outside but inwardly leave us in the same place.

So let sadhana be a turning the tables round within the structure of our own mind, a vital transvaluation of values, a change in the very outlook of our life. The whole secret is in our hands. The magic is in our own internal approach while the Guru, or whatever he is, is an instrument in the same way as the working of an extraneous medicine in our personality. But the vitality in us has to cooperate. A corpse will not react to any medicine that is thrust into it. The vital force in the body of a person is the main factor which contributes to the cure of illness. If the vital force is absent, medicines cannot work. The medicines are the Gurus, but we have to cooperate.

If we are non-receptive and stubborn in our outlook of life, if we stick to our own guns whatever happens anywhere, then there is no movement of the boat of life. We will be rowing the boat of life endlessly throughout the night of ignorance while the boat is tied to a peg, as an old story goes. The boat is tied, anchored. Due to the liquor of life that we have drunk abundantly, making us giddy and oblivious of all things, we have forgotten to lift the anchor. We try to row the boat of life towards God, but the boat has not moved one inch because the anchor has not been lifted. The anchor is the stubborn identification of our ego to this body. The body is the ego, that we think we are this person and that only the sensations of this individuality are worthwhile in life.

Therefore, a complete rapprochement of the whole outlook of our life has to be effected which, in a few words, the Bhagavadgita tells us in the Fifteenth Chapter.

To be continued--

by Swami Krishnananda.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment